Glacier Navigation Errors Compass vs GPS Signal Drift at 70°N

In the rugged and challenging terrain of the polar regions, accurate navigation is crucial for both scientific research and human safety. One of the most challenging environments to navigate is the polar ice caps, where the natural features are often obscured by thick snow and ice. One of the key tools used for navigation in such conditions is the compass. However, with the advent of GPS technology, there has been a shift in how these tools are used. This article will explore the differences between compass and GPS navigation, particularly in the context of signal drift at 70°N, and how these errors can impact glacier navigation.

Compasses have been used for centuries as a reliable means of navigation. They rely on the Earth’s magnetic field to align themselves, providing a clear and unambiguous indication of true north. However, in the polar regions, the Earth’s magnetic field is not as straightforward as it is elsewhere. The magnetic field becomes distorted by the presence of the planet’s iron core and the movement of molten iron within it. This distortion is known as the magnetic declination and can vary significantly from place to place, especially near the poles.

In the Arctic, the magnetic declination can vary from 0° to as much as 20°. This means that a compass needle will not always point directly to true north but will instead align with the magnetic north. This discrepancy can lead to navigation errors, especially when trying to navigate along the coast or across large ice sheets like glaciers.

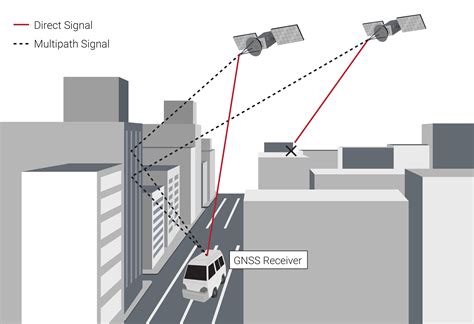

GPS, on the other hand, uses satellite signals to determine position. While GPS is a more precise tool than a compass, it is not without its limitations. One of the primary concerns with GPS in polar regions is signal drift. This phenomenon occurs due to the bending of GPS signals as they pass through the Earth’s atmosphere and the ionosphere, which is a layer of charged particles in the upper atmosphere.

At 70°N, signal drift can be particularly pronounced. The ionosphere is more dense at higher latitudes, which causes the GPS signals to bend more, leading to a larger deviation from the expected position. This drift can be as much as 10% of the distance traveled, which is significant in the vast distances covered by glaciers.

When comparing the two navigation methods, it becomes clear that neither is perfect. Compasses can suffer from magnetic declination errors, while GPS is susceptible to signal drift. To mitigate these errors, navigators must use a combination of both tools and apply corrections based on local conditions.

For example, a navigator using a compass at 70°N would need to adjust the reading based on the local magnetic declination. Similarly, a GPS user would need to apply corrections for signal drift. Additionally, combining the two methods can provide a more accurate navigation solution. By overlaying the compass reading with the GPS position, navigators can cross-reference the data and reduce the likelihood of errors.

In conclusion, glacier navigation at 70°N presents unique challenges due to the combination of magnetic declination and signal drift. While compasses and GPS each have their limitations, using a combination of both can help mitigate these errors. As technology continues to advance, it is likely that new methods and tools will emerge to improve navigation in polar regions, making the task of navigating the treacherous terrain of the polar ice caps safer and more efficient.